Sutriyan: On Being Fed

Mojo Jojo is on a rampage, yet again.

Laser beams shoot out of his eyes as he attempts to conquer Townsville. My eyes are glued to the screen hovering above me. I know he won’t succeed. He never does. Even so, I dig my palms into the futon and lean my head forward in anticipation, my mouth agape.

I am hungry.

At this stage in life, food is simple. I desire it, but I don’t yet understand it. I know how instant noodles are made. I know how french fries are made. That’s about it.

A spoon heads straight for my mouth.

It appears without ceremony, without explanation. It is simply there. Warm. Deliberate. Inevitable.

This is how care first arrives in my body: quietly, without asking me to name it.

Sutr means thread. A string. A strand.

On its own, sutr is not a particularly sturdy word. It must be wound and stretched, coaxed and held.

This process gives birth to Sutriyan (soot-tri-yaan)

For a long time, they were a mystery for me. I simply remembered their taste – savoury, warm, chewy.

Feeling precedes naming.

I encountered them again when I was sixteen, sometime after midnight. I had spent the day on my feet, cashing people out, counting change, wiping down counters. When it was quiet, I hid in the back room with my biology notes spread across a crate, memorizing diagrams I hadn’t made sense of yet.

I was tired, with a hunger that felt dull rather than sharp.

When the bowl was placed in front of me, I recognized texture first.

In Deccani Hyderabadi cuisine, sutriyan are the underdogs.

They are not particularly boastful or debonair, like Hyderabadi haleem or biryani, nor are they complex or misunderstood, like sheer korma or baghaar-e-baingan.

Sutriyan are, traditionally, a way of using what already exists. Leftover rotis. A pot of broth that’s been simmering quietly. The kind of meal that assumes more than one body in the house, more than one plate on the table.

We don’t live like that.

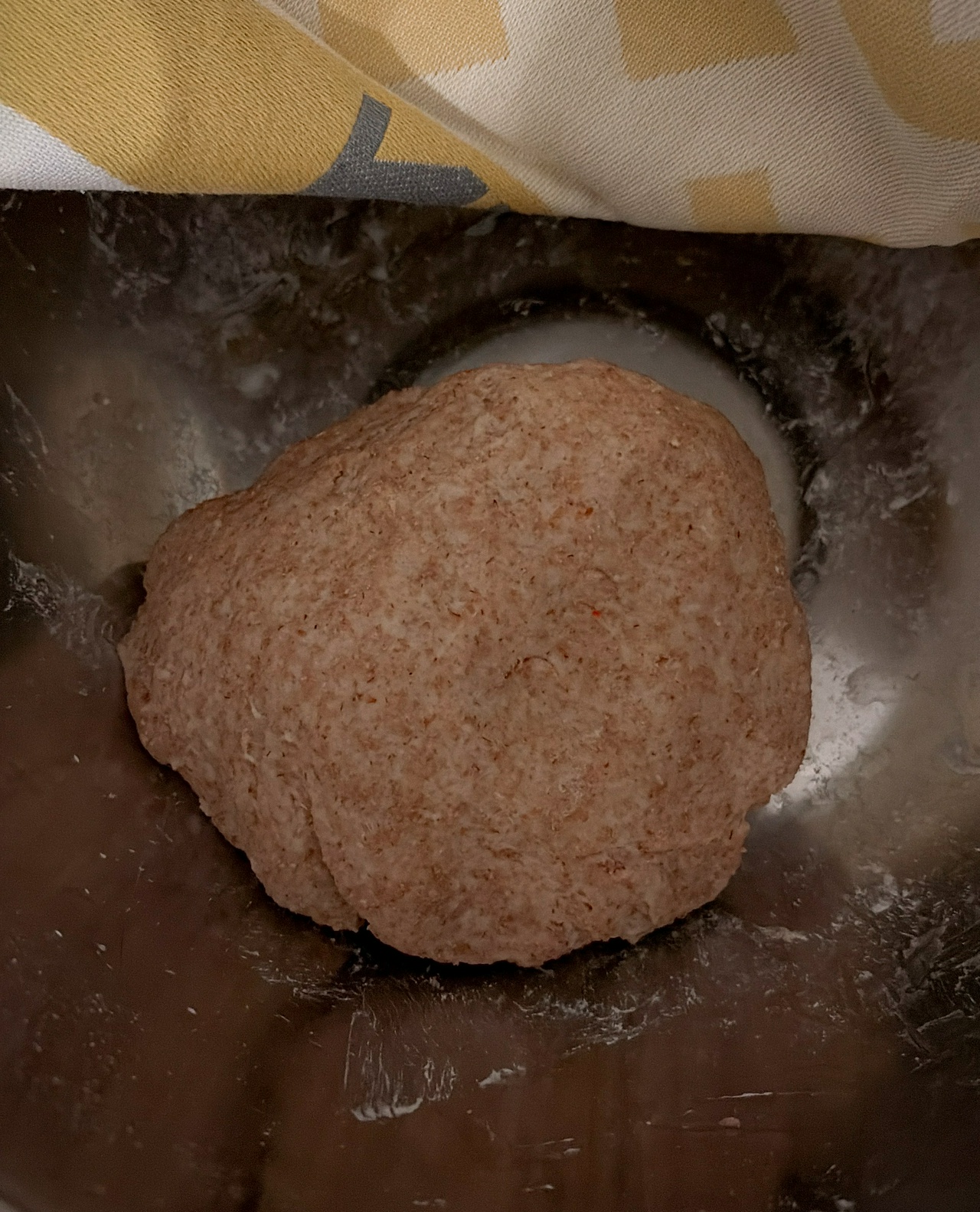

There are no leftover rotis here. There is nothing waiting in the fridge to be repurposed. So I knead the aata myself. Roll the dough. Cook fresh rotis one by one, only to tear them apart again.

I create the conditions the dish requires in a space that does not naturally produce them.

The process takes nearly two hours.

Halfway through, I can’t shake the feeling that I have worked against the grain of the recipe rather than with it. I turned something meant to be economical, collective, and quiet into a small act of insistence.

Time stretches before us, and tiny fissures occupy the spaces left behind.

In another life, this recipe would have taken fifteen minutes. In another life, there would have been leftover rotis folded into a cloth, a pot already half-full, a house calibrated for reuse. Instead, I work slowly, deliberately, recreating a logic that no longer fits how we live.

My mind latches onto a memory fraying at the seams; it clings to a world that precedes distance and precedes efficiency. Once you’ve spotted fracture lines within a structure, it’s difficult to pretend they aren’t there. You can still show up. You can still participate. But the spirit, the assumed camaraderie, no longer arrives on its own.

The cooking does not stop, although some ingredients are missing.

Halfway through, my fiancé runs out to grab paneer – an errand that takes five minutes because the grocery store is directly across the street from us. Walkable. Casual. A form of convenience I haven’t experienced in many years, and am only now learning to value. He returns without ceremony, slipping back into the apartment as though he never left.

In the meantime, our kitten discovers the stovetop.

He jumps up with the confidence of someone who has unlocked a new level. I scoop him up, gently lower him to the ground – and make stern eye contact to show him that this isn’t okay.

He does it again.

This, too, becomes a game – one I protest, one I secretly enjoy.

The yogurt waits in the bowl. I lower the heat. My hand hesitates before stirring it into the onion-tomato mixture, my heart thudding with the unreasonable fear that it will curdle and ruin everything.

It doesn’t.

Sounds emerge from the living room: a vlog of an Uber Eats driver. Youtube content floods our home like a makeshift ritual. We don’t discuss why. We don’t need to. Slowly, and without much fanfare, time does what it does best when we stop rushing it.

The two hours are arduous, yes. But they are also charged.

By small returns. By new habits. By interruptions I don’t resent.

When we finally sit down, our bowls are modest. Two spoons. A tiny table. A mini can of Pepsi Zero sweating onto the surface.

Nothing about this resembles the world that sutriyan were designed for.

And yet.

Care still finds a way in.

My partner raises a spoonful to his mouth. I hold my breath, my eyes tracking every micro expression on his face.

He sinks his spoon into the bowl for another bite before lightly remarking:

“There will be no leftovers tomorrow, I’m going to finish this tonight.”

My thoughts pause mid motion, and hunger dissipates:

sans fanfare,

sans abundance,

sans efficiency.

I have been fed.